IB Economics PPC Explained

IB Economics PPC explained with real-world analogies, trade-offs, and graph insights. Learn why every economic choice comes with a cost.

IB ECONOMICS HLIB ECONOMICSIB ECONOMICS SLIB ECONOMICS INTRODUCTION

Lawrence Robert

5/13/20254 min read

The Production Possibility Curve (PPC): A Fancy Graph About Life Being Unfair

We’ve talked about scarcity, choice, and how you can’t have unlimited pizza. Now, it’s time to look at the graph that makes all of that painfully visible: the Production Possibility Curve.

This is one of the first real diagrams you’ll master in IB Economics, and it shows you just how rough life can get when resources are limited and choices have consequences.

Let’s dive in.

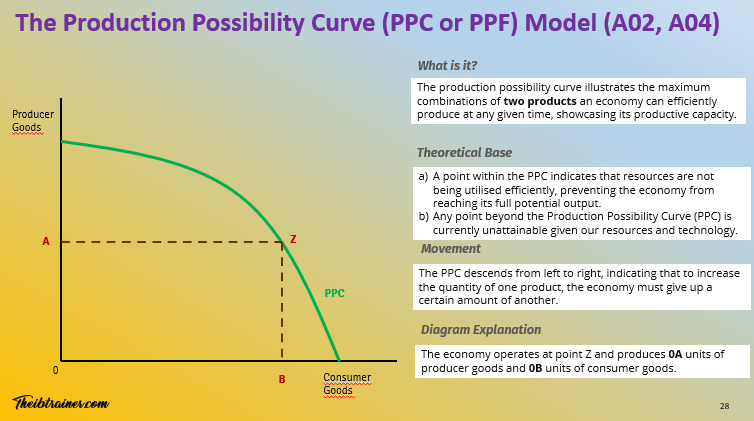

IB Economics What Is the PPC?

The PPC (sometimes called PPF for “Production Possibility Frontier”) shows the maximum combination of two goods an economy can produce when it's using all its resources efficiently.

Think of it like a workout schedule:

More time on cardio = less time for strength training

More Netflix = less studying

More tanks = fewer hospital beds

Every choice has a cost. This graph makes that painfully clear.

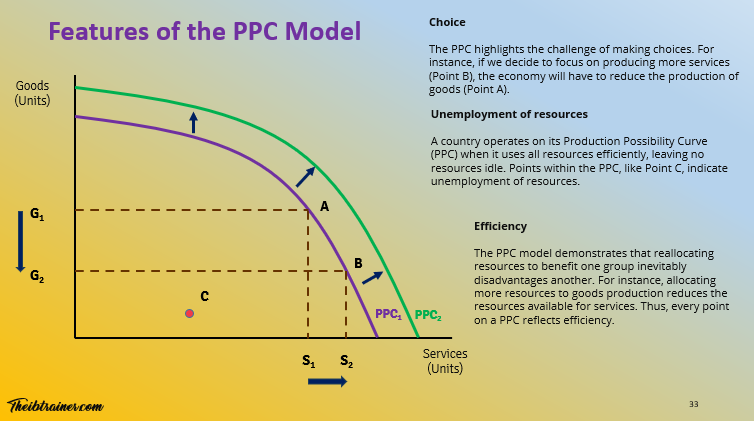

Points on the Curve: What They Mean

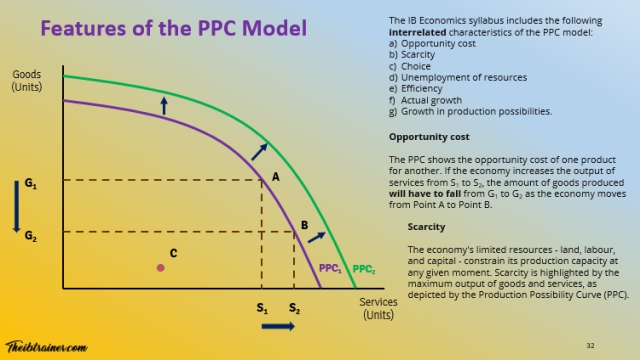

Let’s say your economy makes only two things: capital goods (like machines and factories) and consumer goods (like burgers and video games). Here's what the curve tells you:

Point ON the curve (Point A): Maximum efficiency. Everyone’s working, nothing’s wasted. Gold star.

Point INSIDE the curve (Point C): Underperforming. Some resources are unemployed - maybe the economy’s in a recession or people are on strike.

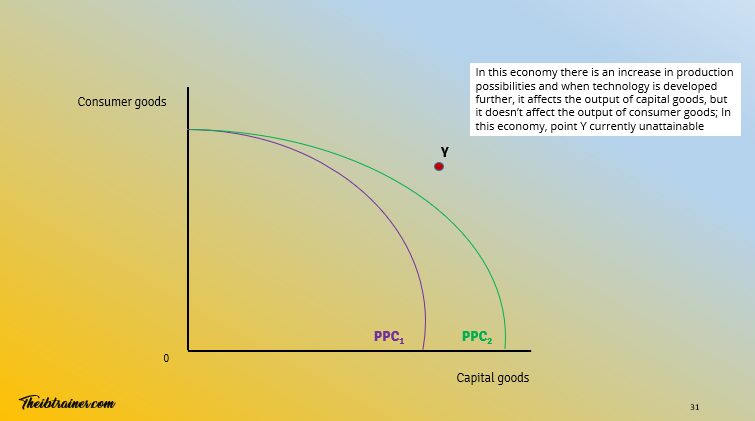

Point OUTSIDE the curve (Point Y): Lovely idea, but not currently possible. Unless your country suddenly discovers a magical unicorn that boosts production, you can’t get there. Yet.

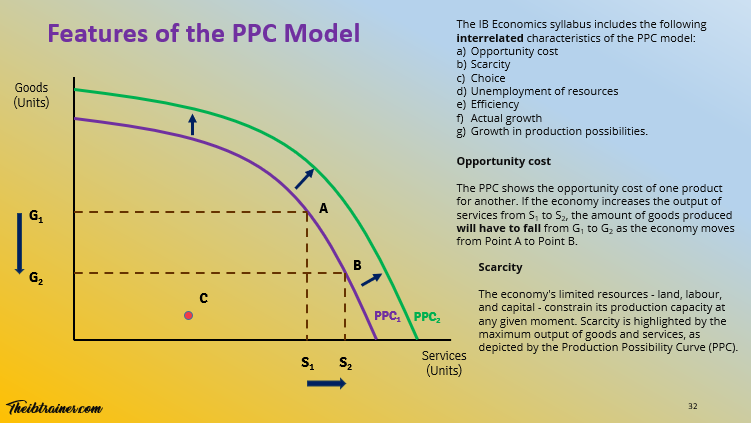

The Big Trade-Off: Opportunity Cost in Action

If you move from Point A to Point B on the curve, and produce more consumer goods, you lose some capital goods. That loss? That’s your opportunity cost.

Example:

Increase services from S1 to S2?

You must reduce goods from G1 to G2.

That’s Economics 101: you can’t have it all.

And the shape of the curve matters, too...

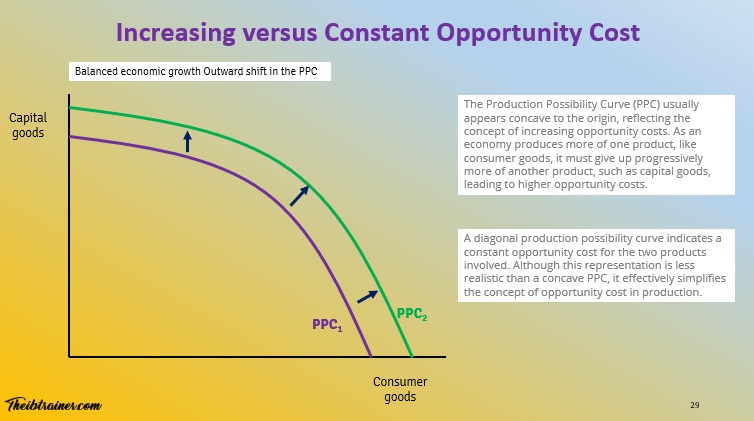

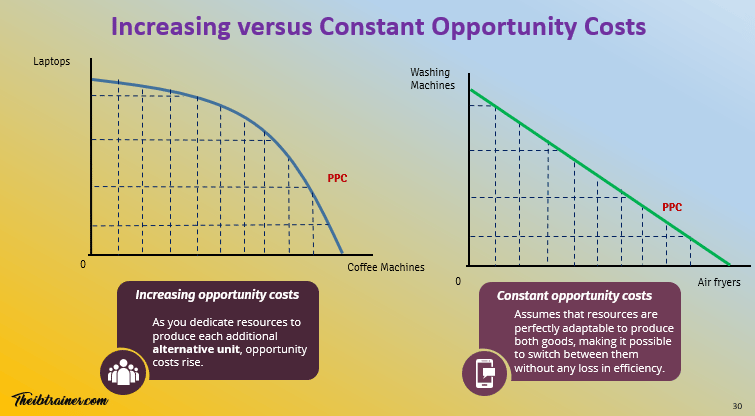

Constant vs Increasing Opportunity Cost in your IB Economics Course

Straight-line PPC = constant opportunity cost

(Very tidy. Not very realistic.)Curved PPC (concave to the origin) = increasing opportunity cost

(More realistic: some workers are better at making shoes than coding apps. Swapping them means you lose efficiency.)

The more you produce of one good, the more you must sacrifice of the other. Welcome to real life.

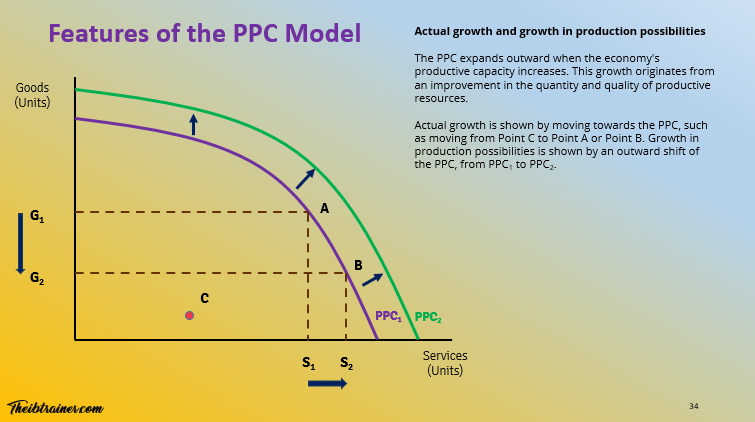

Shifts in the PPC in IB Economics: When the Economy Gets Gains (or Not)

The curve can shift. Here’s how:

Shift outward = growth.

➤ New tech, better education, more natural resources.

➤ Example: investing in renewable energy = more output potential.Shift inward = decline.

➤ War, pandemic, brain drain.

➤ Example: A major drought wipes out agriculture → PPC moves in.

Sometimes the curve shifts non-parallel - when growth only affects one good (e.g. tech helps capital goods but not services). You’ll love drawing this in your IB Economics exams.

Actual Growth vs Potential Growth

This one’s in the syllabus, and examiners love it.

Actual growth = moving from inside the curve to on it

➤ Example: Getting people back to work after a recessionPotential growth = the whole curve moves outward

➤ Example: Investing in education boosts productivity long-term

Key Features of the PPC Model (You’ll Be Quizzed on These)

✔ Scarcity - You can’t produce beyond the curve

✔ Choice - You have to pick a point on the curve

✔ Opportunity cost - Moving from A to B costs something

✔ Efficiency - Every point ON the curve = max output

✔ Unemployment - Any point inside the curve

✔ Economic growth - Curve shifts right

✔ Trade-offs - There’s no such thing as a free lunch

Assumptions of the PPC Model for Your IB Economics Course

Just so you’re aware (and so you don’t scream at the graph):

Only two goods are produced (even though real economies produce millions)

Resources are limited

Technology is fixed

Efficiency is assumed

The PPC only shows the best we can do - no room for laziness

Every episode of Pint-Sized links back to what matters most for your IB Economics course:

Understanding key IB Economics concepts

Applying them in real-world IB Economics contexts

Building IB Economics course confidence without drowning in dry theory.

Subscribe for free to exclusive episodes designed to boost your IB Economics grades and confidence:

Real-World Example for your IB Economics Course

During COVID, governments had to make PPC-style trade-offs between:

Investing in healthcare

Keeping the economy open

Funding stimulus or aid packages

The choices weren’t just theoretical - they impacted lives, unemployment, inflation, and global supply chains. That’s why this graph matters.

For access to all IB Economics exam practice questions, model answers, IB Economics complete diagrams together with full explanations, and detailed assessment criteria, explore the Complete IB Economics Course:

Final Thought for your IB Economics Course

If you’ve ever had to decide between revising for IB Economics or going to a party…

If you’ve ever bought one thing instead of another…

If you’ve ever wondered why governments can’t fix everything all at once…

IB Economics Diagrams Programme, What's included:

200+ exam-ready diagrams covering the entire IB Economics syllabus

Video for every diagram showing you exactly how each model looks

Image version perfect for modelling diagrams in you essays, presentations, and your IA

Detailed written explanations of the IB Economics theory behind each diagram

Both SL and HL IB Economics diagrams clearly labelled and organised by topic

Real IB Economics exam application showing how to use diagrams effectively in Paper 1 and Paper 2

Congratulations. You’ve lived the PPC.

© Theibtrainer.com 2012-2026. All rights reserved.

More Basic Resources For IB Students:

Legal

Have a Tip? Send us a tip using our anonymous form