IB Economics Oligopoly Collusion And Game Theory

Oligopolies, collusion, price wars, and Game Theory - explore the strategic world of Market Power Part 4 for IB HL Economics.

IB ECONOMICS HLIB ECONOMICSIB ECONOMICS MICROECONOMICS

Lawrence Robert

4/14/20253 min read

Oligopoly, Collusion, and the Game Theory Mind Games

Imagine four burger chains selling in a small city. One lowers prices. The rest panic. Then one boosts advertising. Another launches a new "limited edition" pineapple chilli mayo burger. Things escalate quickly.

The description above fits quite well the world of oligopoly - a market ruled not by hundreds of tiny firms, but by a few big players constantly watching, reacting, and sometimes… colluding.

IB Economics What Is an Oligopoly?

An oligopoly is a market structure where a small number of large firms dominate. Each has market power, and their power dynamics are quite intense.

Two Faces of Oligopoly in your IB Economics Course

1. Collusive Oligopoly

Firms work together - formally or informally - to limit competition.

Why? It boosts profits. If all firms raise prices together or restrict output, they create artificial scarcity.

This can form a cartel, like the OPEC coordinating oil output.

Problem? It’s illegal in many countries. And hard to prove, especially in cases of tacit collusion (silent agreement, no paper trail).

2. Non-Collusive Oligopoly

Firms compete, but they’re watching and "supervising" each other like hawks. No agreement - just strategy.

The danger? Price wars. One firm cuts prices, others retaliate. Everyone bleeds profit.

The temptation? Cheat on collusion. If Firm A secretly undercuts prices, they steal customers - at least until the others catch on.

Game Theory: Where IB Economics Meets Chess

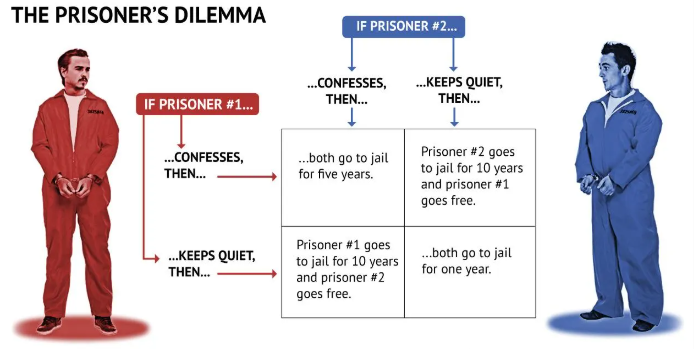

You can't talk about oligopoly without mentioning Game Theory - specifically the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Developed in the 1950s by John Nash, Game Theory shows that:

Rational behaviour can lead to irrational outcomes.

Firms trying to outsmart each other may all end up worse off.

Collusion can maximise profits… but only if no one cheats.

The Nash Equilibrium

This is the point where no firm changes strategy - because doing so wouldn't help, given the other's choice.

IB Economics Example:

Two firms can choose to collude or compete. If both collude, they both win. But if one cheats, they win big and the other loses. But if both cheat - everyone loses.

Price Competition: The Downward Spiral

Oligopolies sometimes fight on price - but it’s risky.

Why?

Everyone’s watching. A price cut triggers retaliation.

It’s easy to match a price cut. Harder to win a price war.

Common Price Tactics:

Introductory pricing (low initially to generate market traction and to gain market share)

Undercutting rivals

Discounts for bulk purchases

“Everyday low prices” tactics

But often price tactics turn into a race to the bottom - so firms look elsewhere…

Non-Price Competition: The Real IB Economics Battlefield

This is where oligopolies shine - in product features, branding, and marketing genius.

IB Economics Real-life Examples include:

Coca-Cola vs Pepsi: Years of ads, celebrity endorsements, and Christmas trucks

Apple vs Samsung: Features, design, exclusivity, and a lot of innovation

McDonald’s vs Burger King: Menu tweaks, loyalty apps, and limited editions (remember the BTS Meal?)

Top Non-Price Moves:

Branding and image-building

Product development (limited editions, upgrades)

Slick packaging

Customer service

Advertising everywhere (from YouTube, to bus stops)

Interdependence: It’s All About Reactions

In oligopoly, every move is calculated - because one firm’s decision affects everyone else. It’s economic chess, not checkers.

If one brand launches a “Buy One Get One Free” deal, others might do the same.

If one firm introduces a new product feature, rivals will match it or beat it.

This interdependence is why price changes are sticky and have the ability to remain - it’s risky to be the first mover.

For access to all IB Economics exam practice questions, model answers, IB Economics complete diagrams together with full explanations, and detailed assessment criteria, explore the Complete IB Economics Course:

Market Failure and Oligopoly

Oligopolies often lead to:

Allocative inefficiency – Prices exceed marginal cost (P > MC)

Restricted output – Firms produce less to drive up price

Reduced consumer choice – Especially in collusive settings

Anti-competitive behaviour – Illegal cartels, price-fixing, or predatory pricing

That’s why governments regulate oligopolies - monitoring for competition abuse and promoting transparency.

Every episode of Pint-Sized links back to what matters most for your IB Economics course:

Understanding key IB Economics concepts

Applying them in real-world IB Economics contexts

Building IB Economics course confidence without drowning in dry theory.

Subscribe for free to exclusive episodes designed to boost your IB Economics grades and confidence:

Recap for your IB Economics Course: The Oligopoly Survival Guide

A few firms hold major power

They may collude or compete - but both have risks

Game theory explains strategic decision-making

Price wars are dangerous, so firms rely on non-price competition

The market is interdependent, reactive, and always evolving

IB Economics Diagrams Programme, What's included:

200+ exam-ready diagrams covering the entire IB Economics syllabus

Video for every diagram showing you exactly how each model looks

Image version perfect for modelling diagrams in you essays, presentations, and your IA

Detailed written explanations of the IB Economics theory behind each diagram

Both SL and HL IB Economics diagrams clearly labelled and organised by topic

Real IB Economics exam application showing how to use diagrams effectively in Paper 1 and Paper 2

Coming Up: Market Power – The final entry

We’ll wrap up the series by covering Monopolistic Competition, Market Concentration, and Evaluating Big Market Power.

Stay well,

Explore Topics:

IB Economics Module 2 Microeconomics Page

IB Economics Market Power Page

Read Next: IB Economics Profit Revenue and Costs

© Theibtrainer.com 2012-2026. All rights reserved.

More Basic Resources For IB Students:

Legal

Have a Tip? Send us a tip using our anonymous form