Introduction to Economics

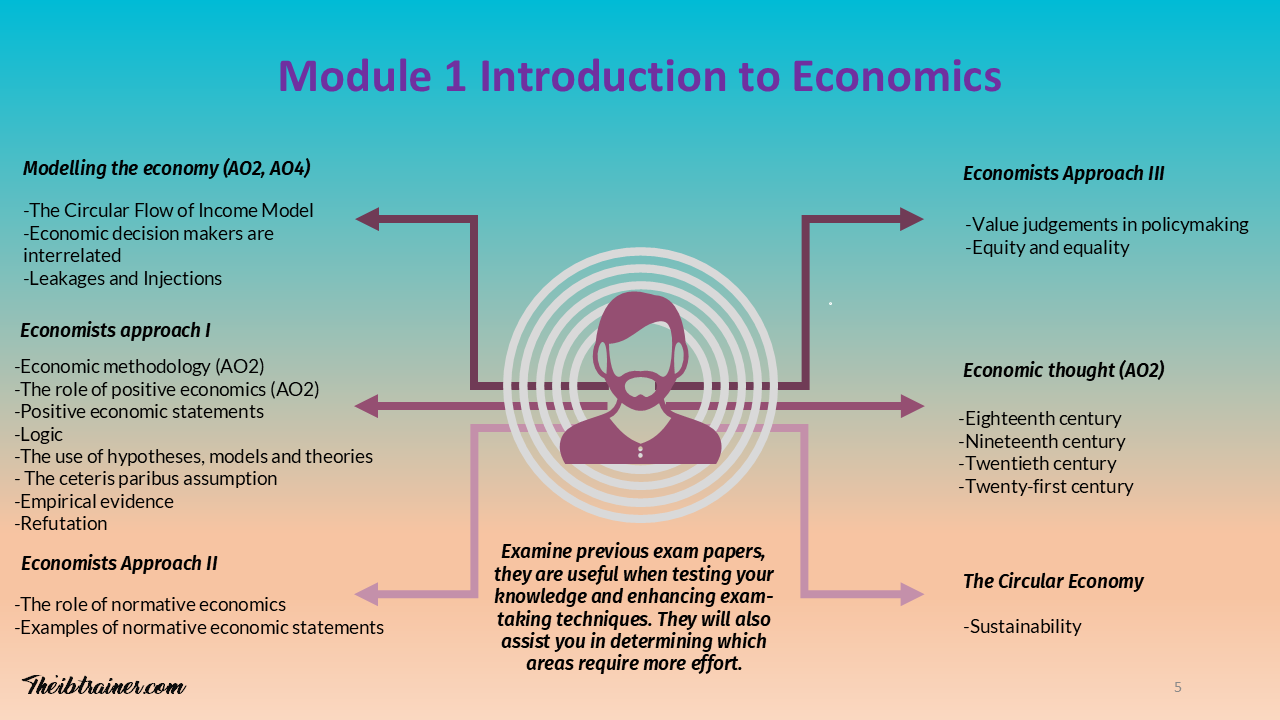

Your complete foundation in IB Economics - from what economics is as a social science through scarcity, opportunity cost, and the PPC model to economic methodology, positive vs normative economics, the nine key concepts, circular flow model, and the evolution of economic thought

Introduction to Economics forms the essential foundation of the entire IB Economics course, providing the conceptual frameworks, analytical tools, and ways of thinking that underpin all subsequent economic analysis. With global challenges from climate change affecting 3.6 billion people to income inequality where the richest 1% own 45% of global wealth to resource scarcity driving conflicts worldwide, understanding how economists think about choices, trade-offs, and resource allocation has never been more critical. This comprehensive introduction explores what economics studies, why scarcity forces choices creating opportunity costs, how economists model economies, what distinguishes positive from normative economics, how the nine key concepts frame economic analysis, and how economic thought has evolved from Adam Smith to contemporary debates. The 2022 syllabus emphasises real-world application, critical thinking about economic methodology, and the nine key concepts that structure the entire course.

What You'll Master:

Complete understanding of economics as a social science studying human behaviour and choices

Deep knowledge of the four factors of production (CELL - Capital, Enterprise, Land, Labour) and their role in creating goods and services

Sophisticated grasp of scarcity as the fundamental economic problem forcing choices with opportunity costs

Advanced understanding of the three basic economic questions: What to produce? How to produce? For whom to produce?

Comprehensive mastery of the Production Possibility Curve (PPC) model showing trade-offs, opportunity costs, and efficiency

Strategic insight into the six real-world issues connecting IB Economics to contemporary challenges

Deep understanding of the nine key concepts (WISE ChoICES: Well-being, Interdependence, Scarcity, Efficiency, Change, Intervention, Equity, Sustainability, Choice) structuring economic analysis

Complete knowledge of the Circular Flow of Income Model showing economic relationships, leakages, and injections

Critical evaluation of positive vs normative economics and the role of value judgements in policymaking

Advanced understanding of economic methodology including hypotheses, models, theories, ceteris paribus, and empirical evidence

Comprehensive overview of economic thought evolution from eighteenth century through contemporary thinking

Strategic understanding of circular economy and sustainability principles

Introduction to Economics comprises approximately 15-20 hours of foundational study, establishing the conceptual toolkit used throughout the course. These fundamental concepts - particularly scarcity, opportunity cost, the PPC model, and the nine key concepts - appear in every subsequent topic from microeconomics through macroeconomics to international trade and development. Understanding how economists think, distinguishing positive from normative statements, and applying the conceptual lenses are essential skills for achieving top grades.

Full breakdowns of introductory economics theory with contemporary examples, concept application, diagram construction, and critical thinking exercises are available in our added value IB Economics resources.

Current Economics Context (2024-2025)

The Scarcity Crisis

Resource scarcity has intensified across multiple areas during 2020-2025. IB Economics Real-life examples: Water scarcity affects 2 billion people globally, with Cape Town, São Paulo, and Chennai experiencing "Day Zero" crises. Energy security concerns drove oil prices from $20 (2020) to $120 (2022) per barrel. Semiconductor shortages during 2020-2023 disrupted automobile production globally, demonstrating how scarcity of one input affects entire industries. Food insecurity increased as Ukraine conflict disrupted 30% of global wheat exports, with 345 million people facing acute food insecurity by 2024.

The Inequality Challenge

Global inequality reached extreme levels, with the richest 1% owning 45% of global wealth while the poorest 50% own just 1%. IB Economics Real-life examples: within countries, inequality increased in most OECD nations, with the top 10% earning 9.5 times more than the bottom 10% on average. The UK Gini coefficient rose from 0.25 (1980) to 0.35 (2024). This inequality represents fundamental questions about "For whom to produce?" - one of the three basic economic questions every society must answer.

The Sustainability Imperative

The circular economy concept gained urgency as linear "take-make-dispose" models prove unsustainable. Global material extraction reached 100 billion tonnes annually, while only 8.6% of materials are recycled. Climate change - the ultimate sustainability challenge - requires transforming how economies answer the basic questions, with global temperatures already 1.2°C above pre-industrial levels and 2024 on track to be the warmest year on record.

What is Economics?

Economics is a social science studying how individuals, businesses, governments, and societies make choices about allocating scarce resources to satisfy unlimited wants and needs. Unlike natural sciences studying physical phenomena, economics examines human behaviour and decision-making, making it inherently less predictable. Economics analyses production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services, addressing fundamental questions about resource allocation.

As a social science, economics uses scientific methodology - developing theories, testing hypotheses, gathering evidence - while recognising that human behaviour involves psychological, social, and cultural factors beyond pure rationality. The 2008 financial crisis, which economists largely failed to predict, demonstrated both economics' value in understanding market mechanisms and its limitations in forecasting complex human systems.

Contemporary economics increasingly incorporates insights from psychology (behavioural economics), environmental science (ecological economics), and data science (econometrics) to better understand real-world economic phenomena.

Factors of Production

All production requires four factors creating goods and services, remembered as CELL:

Capital: Man-made resources used in production including machinery, equipment, buildings, and infrastructure. Differs from financial capital (money) - economists focus on physical and human capital enabling production. Global capital stock exceeds $500 trillion, with China's infrastructure investment (8% of GDP annually) demonstrating capital accumulation driving growth.

Enterprise (Entrepreneurship): The factor organising other factors, taking risks, and driving innovation. Entrepreneurs identify opportunities, make decisions, and accept uncertainty. IB Economics Real-life Examples: include Elon Musk (Tesla, SpaceX), Jack Ma (Alibaba), and millions of small business owners worldwide. Entrepreneurship varies across countries due to cultural factors, regulations, and access to capital.

Land: All natural resources including agricultural land, minerals, forests, water, and oil. Fixed in total supply (though quality varies), making land economically significant. IB Economics Real-life Examples: resource-rich countries like Saudi Arabia (oil), Chile (copper), and DRC (cobalt) demonstrate how natural endowments affect economic development, though the "resource curse" shows wealth doesn't automatically follow from abundance.

Labour: Human effort - physical and mental - employed in production. Quality matters beyond quantity, with education and skills (human capital) increasingly important. Global labour force exceeds 3.5 billion people, with China (800 million) and India (600 million) having largest workforces. Demographic shifts - aging populations in developed countries, young populations in Africa - will reshape global labour supply through 2050.

Scarcity and Opportunity Cost

Scarcity - the fundamental economic problem - exists because human wants are unlimited while resources are finite. Even wealthy societies face scarcity, though its form differs (time scarcity, positional goods scarcity). Scarcity forces choices, and every choice involves opportunity cost - the value of the next best alternative foregone.

When a government spends £100 billion on healthcare, the opportunity cost is what else could have been done with those resources (education, infrastructure, defence, or leaving money with taxpayers). When you study economics for 2 hours, the opportunity cost is what you could have done instead (study another subject, work, leisure). Understanding opportunity cost reveals the true cost of decisions extends beyond money to include foregone alternatives.

IB Economics Real-life Examples: include Covid-19 lockdowns trading economic activity (GDP fell 10-20% in many countries) for health protection, government debt spending (£400 billion UK Covid stimulus) creating future tax or spending opportunity costs, and climate action requiring present consumption reduction for future sustainability benefits.

The Basic Economic Questions

All societies must answer three fundamental questions due to scarcity:

What to produce? Which goods and services should be produced given limited resources? Societies constantly choose between consumer goods and capital goods, necessities and luxuries, private goods and public goods. Market economies let consumer demand determine what's produced, while command economies have government planning. Most modern economies are mixed, with markets producing most goods while government provides defence, education, and healthcare.

How to produce? Which production methods and technologies should be used? Choices involve labour-intensive vs capital-intensive production, traditional vs modern technology, and environmentally sustainable vs extractive methods. China shifted from labour-intensive manufacturing toward automation as wages rose. Developed countries increasingly prioritise sustainable production methods despite higher costs.

For whom to produce? How should output be distributed among society members? Market economies distribute based on ability to pay (income and wealth), potentially creating inequality. Governments modify distribution through taxation and transfers. Nordic countries redistribute more (tax 40-50% of GDP) than the US (30%), reflecting different answers to this question.

The Production Possibility Curve (PPC) Model

The PPC model - sometimes called PPF (Production Possibility Frontier) - shows maximum combinations of two goods an economy can produce given fixed resources and technology, illustrating scarcity, choice, opportunity cost, and efficiency.

Key PPC Characteristics:

Points on the curve represent productive efficiency - using all resources fully and efficiently, impossible to produce more of one good without producing less of another. Points inside the curve show inefficiency - unemployment or resource underutilisation. Points outside are currently unattainable given resources and technology. Movement along the curve illustrates opportunity cost - producing more capital goods requires sacrificing consumer goods.

PPC Shape: Concave (bowed outward) curves show increasing opportunity costs - resources aren't equally suited to all production, so shifting resources increases costs. Straight-line PPCs show constant opportunity costs - resources are equally suited to producing both goods (rare in reality).

PPC Shifts: The curve shifts outward with economic growth from increased resources, improved technology, or better education. Natural disasters, war, or depreciation shift curves inward. During Covid-19, many economies temporarily shifted inward as lockdowns idled resources, then shifted outward during recovery.

IB Economics Real-life Examples: include analysing trade-offs between present consumption and investment (capital goods) affecting future growth, healthcare vs other spending during pandemics, and economic growth vs environmental protection requiring production method changes rather than just output changes.

Real-World Issues (RWI) and IB Economics

The IB Economics course connects theory to six real-world issues providing context and relevance:

1. How do consumers and producers make choices in trying to meet their economic objectives? Explores utility maximisation, profit maximisation, and behavioural economics showing systematic deviations from rational choice.

2. When are markets unable to satisfy important economic objectives - and does government intervention help? Analyses market failures (externalities, public goods, asymmetric information, market power) and government policy responses.

3. Why does economic activity vary over time and why is this relevant? Examines business cycles, unemployment, inflation, and macroeconomic policy attempting to stabilise economies.

4. How do governments manage their economy and how effective are their policies? Evaluates monetary policy, fiscal policy, and supply-side policies considering objectives, trade-offs, and effectiveness.

5. Who are the winners and losers of the integration of the world's economies? Investigates globalisation, trade, protectionism, and how integration creates both opportunities and challenges.

6. Why is economic development uneven? Explores why some countries prosper while others remain poor, analysing barriers to development and policy strategies.

These questions structure the course, with specific topics contributing answers through microeconomic analysis (questions 1-2), macroeconomic theory (questions 3-4), and international/development economics (questions 5-6).

The Nine Key Concepts (WISE ChoICES)

Nine concepts provide conceptual lenses for analysing all economic issues, structuring thinking throughout the course:

Scarcity - The fundamental problem forcing choices as wants exceed resources

Choice - Decision-making by economic agents selecting among alternatives

Efficiency - Optimal resource use minimising waste and maximising output from given inputs

Equity - Fairness in distribution considering both equality and justice

Economic Well-being - Material and non-material factors affecting quality of life beyond GDP

Sustainability - Meeting present needs without compromising future generations' ability to meet theirs

Change - Economic conditions, policies, and structures constantly evolve requiring adaptive analysis

Interdependence - Economic agents and economies are interconnected, with actions affecting others

Intervention - Government actions affecting economic outcomes through policies and regulations

These concepts appear throughout the syllabus. For example, analysing minimum wages involves: scarcity (limited employment opportunities), choice (government policy decision), efficiency (potential unemployment creating deadweight loss), equity (helping low-wage workers but potentially harming unemployed), well-being (income effects), interdependence (employers and workers), and intervention (government setting prices).

Modelling the Economy: The Circular Flow of Income

The Circular Flow Model illustrates economic relationships between households and firms in simple economies, then adds government and foreign sectors.

Simple Two-Sector Model: Households own factors of production (land, labour, capital) which firms hire, paying factor incomes (rent, wages, interest, profit). Households use income to purchase goods and services from firms. This creates two circular flows: real flow (factors one direction, goods/services the other) and money flow (factor payments one direction, consumer expenditure the other).

Adding Leakages and Injections: Three-sector models (adding government) and four-sector models (adding foreign sector) introduce leakages removing money from circulation - savings (S), taxes (T), and imports (M) - and injections adding money - investment (I), government spending (G), and exports (X).

When injections equal leakages (I + G + X = S + T + M), the economy is in equilibrium. When injections exceed leakages, the economy expands. When leakages exceed injections, it contracts. This model provides foundation for understanding macroeconomic fluctuations and policy effects.

Economists Approach I: Economic Methodology

Economics uses scientific methodology while acknowledging human behaviour complexity:

Hypotheses, Models, and Theories: Economists develop hypotheses (testable propositions), build models (simplified representations of reality), and test theories (explanations supported by evidence). Models sacrifice realism for clarity - the PPC model assumes only two goods, though economies produce millions.

Ceteris Paribus: "Other things being equal" - economists analyse one relationship while holding other factors constant. When stating "higher prices reduce quantity demanded," we assume ceteris paribus - income, preferences, and other prices remain unchanged. This isolation enables analysing specific relationships in complex systems.

Empirical Evidence: Economists gather data to test theories, using statistics and econometrics. However, controlled experiments are difficult (can't randomly assign countries to policies), so economists often use natural experiments, historical data, and statistical techniques to infer causation from correlation.

Refutation: Following Karl Popper's scientific philosophy, theories can never be proven definitively but can be refuted by contradictory evidence. The 2008 financial crisis refuted aspects of efficient market theory, leading to revised models incorporating behavioural factors and systemic risk.

Economists Approach II: Normative vs Positive Economics

Positive Economics describes what is, making objective statements testable with evidence. "Unemployment rose to 5.2% in 2024" and "Minimum wage increases reduce employment in competitive markets" are positive statements - we can verify them with data (though causation may be debated).

Normative Economics describes what ought to be, involving value judgements about desirability. "Unemployment is too high" and "Government should raise minimum wage" are normative statements - they reflect opinions about desirable outcomes. We can't prove normative statements true or false through evidence, as they depend on values and priorities.

Most economic debates involve both types. Positive economics analyses consequences: "Carbon taxes will reduce emissions by X% and cost Y." Normative economics judges whether this trade-off is desirable: "We should implement carbon taxes despite costs." Disagreements often stem from different normative judgements (how much we value present vs future, efficiency vs equity) rather than positive analysis.

Economists Approach III: Value Judgements and Policymaking

Economic policymaking inevitably involves value judgements about priorities and trade-offs. When inflation and unemployment trade off (Phillips curve), which should government prioritise? The answer depends on normative views about their relative harm.

Equity vs Equality: Equity (fairness) differs from equality (sameness). Equal treatment (everyone pays same tax) may be unfair if income differs vastly. Equitable treatment might be progressive taxation (higher earners pay higher percentage). Reasonable people disagree about what's fair - equal opportunity vs equal outcomes, individual responsibility vs social support.

Policymakers face value judgements about: present vs future (how much to sacrifice now for future benefits), efficiency vs equity (how much efficiency loss to accept for fairer distribution), individual freedom vs collective welfare (how much to regulate), and environment vs growth (how much environmental protection justifies growth costs).

Understanding these value judgements helps analyse policy debates rationally, distinguishing technical disagreements (positive economics) from value disagreements (normative economics).

Economic Thought Through the Ages

Economic thinking evolved as economies changed:

Eighteenth Century: Adam Smith's "Wealth of Nations" (1776) established economics as discipline, arguing free markets coordinate production through "invisible hand" - self-interest unintentionally promoting social welfare. Classical economics emphasised markets' self-correcting properties and benefits of specialisation/trade.

Nineteenth Century: David Ricardo developed comparative advantage theory explaining trade patterns. Thomas Malthus warned population growth would outstrip food supply (though technological progress proved him wrong). Karl Marx critiqued capitalism's inequality and instability, predicting its collapse (which hasn't occurred, though his analysis influenced policy debates).

Twentieth Century: John Maynard Keynes revolutionised macroeconomics during Great Depression, arguing market economies can experience prolonged unemployment requiring government intervention. Milton Friedman and monetarists later challenged Keynesian policies, emphasising monetary policy and markets' efficiency. The century saw debates between these perspectives shape policy.

Twenty-first Century: Behavioural economics (Daniel Kahneman, Richard Thaler) incorporated psychology, showing systematic deviations from rationality. Ecological economics emphasised environmental constraints. The 2008 financial crisis triggered rethinking of financial regulation, inequality concerns, and capitalism's sustainability. IB Economics Real-life Examples focus on inequality, climate change, technological disruption, and whether capitalism can address these challenges.

The Circular Economy and Sustainability

The circular economy concept reimagines production and consumption to eliminate waste and maximise resource use, contrasting with linear "take-make-dispose" models. Key principles include designing out waste, keeping materials in use longer, and regenerating natural systems.

Currently, only 8.6% of materials are recycled globally, with 100 billion tonnes of materials extracted annually. The circular economy aims to increase this through product design for durability and recyclability, sharing economy models (car-sharing reducing vehicles needed), remanufacturing and refurbishment, and industrial symbiosis (one industry's waste becoming another's input).

IB Economics Real-life Examples: The Netherlands targets 50% circularity by 2030, implementing policies supporting circular business models. Companies like Patagonia (repair services), Philips (lighting-as-a-service), and Interface (carpet tile recycling) demonstrate circular approaches. However, challenges include higher upfront costs, consumer preference for new products, and technological limitations in recycling complex products like smartphones.

Circular economy connects to sustainability - economic activity maintaining prosperity while protecting environment for future generations - one of the nine key concepts structuring IB Economics analysis.

IB Economics Topic Integration

Introduction to Economics concepts appear throughout the course. The PPC model illustrates trade-offs in microeconomics (production choices), macroeconomics (unemployment vs inflation), and international economics (trade benefits). Opportunity cost underlies all economic decisions from consumer choice to government policy. The nine key concepts provide analytical lenses for every topic. Understanding positive vs normative economics enables critical policy evaluation. The circular flow model provides foundation for macroeconomic analysis.

Every subsequent topic applies these foundational concepts - scarcity, opportunity cost, efficiency, equity - in specific contexts. Mastering the introduction to economics module enables sophisticated analysis throughout the course.

Key Concept Application

The nine key concepts structure economic thinking:

Scarcity forces every economic decision - from individual choices to government priorities

Choice involves weighing alternatives and opportunity costs in all contexts

Efficiency provides criterion for evaluating resource allocation in markets and policies

Equity raises questions about fairness in distribution requiring value judgements

Economic Well-being reminds us GDP isn't the only measure of success

Sustainability requires considering long-run environmental and social impacts

Change means economic analysis must account for evolving conditions and technologies

Interdependence shows actions affect others, requiring considering spill over effects

Intervention questions when government intervention should take place and what policies work best

Study Progression Strategy

Foundation Building (Weeks 1-2)

Master core concepts: scarcity, opportunity cost, factors of production, basic economic questions, and the PPC model. Practice diagram construction and opportunity cost calculations.

Conceptual Development (Week 2-3)

Understand the nine key concepts, distinguish positive from normative economics, and analyse the circular flow model. Practice applying concepts to IB Economics real-world examples.

Integration and Application (Week 3+)

Connect foundational concepts to subsequent topics. Use the nine concepts as analytical lenses. Distinguish positive from normative statements in policy debates. Apply PPC and circular flow models to contemporary issues.

For Optimal Introduction to Economics Success:

Master the PPC model: practice drawing, calculating opportunity costs, and showing shifts

Memorise the nine key concepts (WISE ChoICES) and practice applying them to any economic issue

Distinguish positive from normative statements in every policy debate

Understand opportunity cost appears in every economic decision

Connect foundational concepts to real-world examples: scarcity (water, semiconductors), choice (government priorities), trade-offs (PPC)

Recognise value judgements underlying policy disagreements

Practice circular flow model showing leakages and injections

Quick Access to Introduction to Economics Topics

What is Economics? - Economics as social science, studying choices and resource allocation

Factors of Production - CELL (Capital, Enterprise, Land, Labour), resource constraints

Scarcity and Opportunity Cost - Fundamental problem, value of next best alternative foregone

Basic Economic Questions - What to produce? How to produce? For whom to produce?

PPC Model - Maximum production combinations, opportunity cost, efficiency, growth

Real-World Issues - Six questions connecting theory to contemporary challenges

Nine Key Concepts - WISE ChoICES providing analytical lenses throughout course

Circular Flow Model - Economic relationships, leakages, injections, equilibrium

Economic Methodology - Hypotheses, models, theories, ceteris paribus, empirical evidence

Positive vs Normative - Objective statements vs value judgements

Value Judgements - Equity vs equality, priorities and trade-offs in policymaking

Economic Thought - Evolution from Smith through Keynes to contemporary debates

Circular Economy - Sustainability, resource use, waste elimination

Why Choose Our Introduction to Economics Hub?

Exam-Focused Content: Every concept designed with IB Economics assessment requirements in mind, ensuring you master the foundational tools used throughout Papers 1, 2, and 3.

Real-World Context: From water scarcity affecting 2 billion people to inequality where top 1% own 45% of wealth to circular economy initiatives, we make foundational concepts concrete through contemporary examples.

Complete Coverage: All introductory topics from what economics studies through the nine key concepts to economic methodology and thought evolution, with guides covering every foundational requirement.

Contemporary Context: Updated with 2024-2025 data on scarcity challenges, inequality trends, and sustainability imperatives.

Think Like an Economist: Develop the analytical reasoning and conceptual thinking that makes economics a powerful tool for understanding resource allocation and policy debates.

Conceptual Mastery: The nine key concepts appear in every topic - mastering them now enables sophisticated analysis throughout the course.

Ready to Master Introduction to Economics?

Start with understanding what economics studies, grasp scarcity and opportunity cost, master the PPC model, learn the nine key concepts (WISE ChoICES), understand the circular flow model, and distinguish positive from normative economics. These foundations enable success throughout IB Economics.

This hub is regularly updated with the latest examples of scarcity, choice, and sustainability challenges to ensure you have the most current information for your IB Economics course.

More information about:

IB Economics Microeconomics Page

IB Economics The Global Economy

Read Next: IB Economics Calculations SL & HL

© Theibtrainer.com 2012-2026. All rights reserved.

More Basic Resources For IB Students:

Legal

Have a Tip? Send us a tip using our anonymous form