Microeconomics

Your complete mastery of IB Economics microeconomics - from fundamental demand and supply theory through market equilibrium, elasticity concepts, government intervention, and market failure analysis including externalities, public goods, asymmetric information, and market power

Microeconomics forms the analytical foundation of the entire IB Economics course, providing the theoretical frameworks and tools essential for understanding how individual consumers and producers make decisions in markets. With global carbon pricing mechanisms now covering over 23% of greenhouse gas emissions and governments worldwide implementing price controls on essential goods, understanding microeconomic principles has never been more critical for analysing real-world policy decisions. This comprehensive microeconomics section explores how markets allocate scarce resources, why prices matter, when markets fail to achieve efficient outcomes, and how government intervention can address - or sometimes worsen - these failures. The 2022 syllabus emphasises real-world applications, contemporary policy debates, and the nine key concepts of scarcity, choice, efficiency, equity, economic well-being, sustainability, change, interdependence, and intervention throughout all topics.

What You'll Master:

Complete understanding of demand and supply fundamentals including determinants, movements, and shifts

Deep analysis of competitive market equilibrium and price mechanisms

Critical evaluation of assumptions underlying rational consumer and producer behaviour (HL only)

Sophisticated application of price, income, and cross elasticity of demand concepts

Advanced understanding of price elasticity of supply and its determinants

Strategic analysis of government microeconomic intervention including price controls, indirect taxes, subsidies, and direct provision

Comprehensive knowledge of market failure theory including negative and positive externalities, common pool resources, and environmental sustainability

Deep insight into public goods and the free-rider problem

Critical evaluation of asymmetric information and its market consequences (HL only)

Advanced understanding of monopoly power and anti-competitive behaviour (HL only)

Sophisticated analysis of income and wealth inequality and market limitations in achieving equity (HL only)

Real-world applications using contemporary case studies from carbon pricing to pharmaceutical patents

Advanced analytical frameworks using diagrams, calculations, and policy evaluation

Microeconomics comprises approximately 30-35 hours at IB Economics Standard Level (SL) and 40-45 hours at Higher Level (HL), making it the theoretical foundation for all subsequent economics units. The concepts developed here - particularly elasticity, market failure, and government intervention - underpin macroeconomic policy analysis, international trade theory, and development economics. The mean grade of 4.8 for IB Economics HL and 4.7 for SL reflects the rigorous analytical thinking this unit develops.

Full breakdowns of microeconomics theory with contemporary case studies, practice calculations, diagram construction, and exam techniques and questions are available in our IB Economics added value resources.

Current Global Microeconomics Context (2024-2025)

The Carbon Pricing Revolution

Carbon pricing mechanisms now cover over 23% of global greenhouse gas emissions, with the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) reaching €80+ per tonne of CO2. Carbon taxes operate in over 30 jurisdictions worldwide, demonstrating real-world application of Pigouvian taxes to correct negative externalities. Global carbon credit markets reached $850 billion in 2024, reflecting growing use of market-based mechanisms to address climate change.

Pharmaceutical Patents and Market Power

The pharmaceutical industry demonstrates extreme market power, with top-selling drugs like Keytruda generating $25 billion annually for Merck. Patent protection creates temporary monopolies enabling companies to charge prices vastly exceeding marginal costs. The average new drug takes 10-15 years and $2.6 billion to develop, justifying patent protection but creating access challenges in developing economies where 2 billion people lack access to essential medicines.

Housing Market Failures

Global housing affordability has reached crisis levels, with house-price-to-income ratios in major cities exceeding 15:1 in Hong Kong, 12:1 in Sydney, and 10:1 in London. Zoning restrictions create artificial supply constraints, while asymmetric information between buyers and sellers affects market efficiency. Government interventions include rent controls (NYC, Berlin), social housing provision, and planning reform debates.

Unit 1: Demand

The law of demand states that as price falls, quantity demanded rises, ceteris paribus, due to the income and substitution effects. Demand curves slope downward, reflecting the inverse price-quantity relationship. Determinants of demand (non-price factors) include income levels, prices of substitutes and complements, consumer preferences, expectations, and number of consumers. Changes in these determinants shift the entire demand curve left or right, while price changes cause movements along the curve.

Contemporary applications include understanding how rising incomes in developing economies increase demand for protein and consumer goods, how changing preferences toward sustainability affect demand for electric vehicles, and how expectations of future price increases drive current demand surges.

Unit 2: Supply

The law of supply states that as price rises, quantity supplied rises, ceteris paribus, as higher prices make production more profitable. Supply curves typically slope upward, reflecting the positive price-quantity relationship. Determinants of supply include production costs (wages, raw materials, energy), technology, prices of related goods, expectations, number of suppliers, and government intervention (taxes, subsidies, regulations).

IB Economics Real-life examples include how energy price shocks affect supply of goods with high energy inputs, how technological advances in solar panel manufacturing shifted supply dramatically rightward reducing prices by 90% over a decade, and how supply chain disruptions during 2020-2023 shifted supply curves leftward creating shortages.

Unit 3: Competitive Market Equilibrium

Market equilibrium occurs where demand equals supply, determining the market-clearing price and quantity. At prices above equilibrium, excess supply creates downward pressure on prices. At prices below equilibrium, excess demand creates upward pressure. The price mechanism automatically moves markets toward equilibrium through these self-correcting forces.

Contemporary examples include labour market equilibrium analysis during the "Great Resignation" of 2021-2023 when excess demand for workers drove wages higher, commodity market equilibrium disruptions following the 2022 Ukraine conflict, and housing market disequilibrium in major global cities where excess demand persists due to supply constraints.

Unit 4: Critique of Maximising Behaviour (HL only)

Traditional microeconomic theory assumes consumers maximise utility and producers maximise profit. However, behavioural economics demonstrates systematic deviations from this assumption. Consumers exhibit bounded rationality (limited information processing), cognitive biases (framing effects, anchoring, loss aversion), herd behaviour, and rules of thumb rather than optimisation. Producers may pursue satisficing rather than maximising, face principal-agent problems, and operate with imperfect information.

IB Economics real-life examples include how consumers systematically undervalue future costs (hyperbolic discounting) leading to excessive borrowing, how framing of choices affects decisions (99% fat-free vs 1% fat), and how corporate managers pursue growth over profit maximisation when shareholder monitoring is weak.

Unit 5: Price Elasticity of Demand (PED)

PED measures responsiveness of quantity demanded to price changes: PED = % change in quantity demanded / % change in price. Elastic demand (PED > 1) means quantity responds strongly to price changes, while inelastic demand (PED < 1) means quantity changes little. Determinants include availability of substitutes, necessity vs luxury, proportion of income, time period, and breadth of definition.

Understanding PED is critical for pricing strategy (maximise revenue where demand is inelastic), tax policy (governments tax inelastic goods like cigarettes and fuel), and subsidy effectiveness (subsidies most effective where demand is elastic). IB Economics Real-world applications include luxury goods with elastic demand, essential medicines with inelastic demand, and addictive goods with highly inelastic demand despite health costs.

Unit 6: Income Elasticity of Demand (YED)

YED measures responsiveness of demand to income changes: YED = % change in quantity demanded / % change in income. Normal goods have positive YED (demand rises with income), with necessities typically 0 < YED < 1 and luxuries YED > 1. Inferior goods have negative YED (demand falls as income rises).

IB Economics real-life examples include understanding how rising incomes in emerging economies shift consumption patterns from rice and staples (necessities) toward meat and processed foods (luxuries), how economic recessions increase demand for inferior goods like budget retailers and discount airlines, and how income inequality affects aggregate demand composition.

Unit 7: Price Elasticity of Supply (PES)

PES measures responsiveness of quantity supplied to price changes: PES = % change in quantity supplied / % change in price. Determinants include spare production capacity, availability of stocks, time period (momentary, short-run, long-run), factor mobility, and ease of entry. Understanding PES is essential for analysing how quickly markets adjust to demand shocks and evaluating tax incidence.

IB Economics real-life examples include agricultural products with inelastic supply in short-run due to production lags, digital products with perfectly elastic supply at near-zero marginal cost, and housing supply with highly inelastic supply in major cities due to land constraints and planning restrictions.

Unit 8: Role of Government in Microeconomics

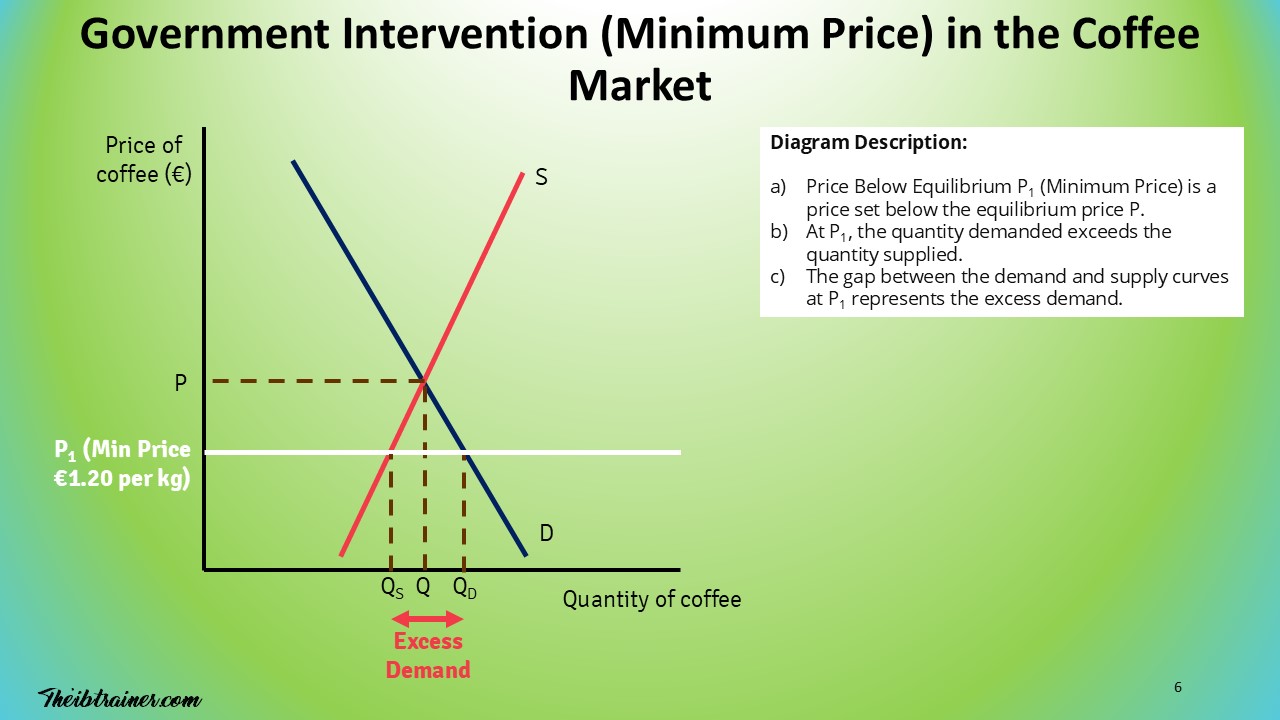

Governments intervene in markets through price controls (maximum and minimum prices), indirect taxes (specific and ad valorem), subsidies, direct provision of goods and services, and legislation/regulation. Price ceilings create shortages, welfare losses, and non-price rationing mechanisms. Price floors create surpluses and require government purchases or production controls.

Indirect taxes shift supply curves leftward, raising prices and reducing quantities with tax incidence depending on relative elasticities. Subsidies shift supply rightward, lowering prices and increasing consumption. IB Economics real-life examples include rent controls in Berlin and New York (price ceilings), minimum wages as price floors in labour markets, carbon taxes on fossil fuels (indirect taxes), agricultural subsidies in EU and USA, and government provision of healthcare and education.

Unit 9: Externalities and Common Pool Resources

Market failure occurs when free markets fail to achieve allocative efficiency or equitable outcomes. Negative externalities (costs imposed on third parties) include pollution, congestion, and health impacts from smoking and alcohol. Positive externalities (benefits to third parties) include education, vaccination, and R&D spill overs. Markets overproduce goods with negative externalities and underproduce goods with positive externalities relative to social optimum.

Government solutions include Pigouvian taxes (carbon taxes, congestion charges), regulations (emission standards, smoking bans), tradeable permits (EU ETS), subsidies for positive externalities (education, renewable energy), and direct provision. Common pool resources (rival but non-excludable) face tragedy of the commons including overfishing, deforestation, and groundwater depletion, requiring regulation, property rights assignment, or community management.

IB Economics real-life examples include climate change as the ultimate negative externality with global carbon pricing reaching $850 billion, plastic pollution with single-use plastic bans in over 70 countries, and antibiotic resistance as healthcare externality requiring regulatory intervention.

Unit 10: Public Goods

Pure public goods are non-rival (one person's consumption doesn't reduce availability to others) and non-excludable (can't prevent non-payers from consuming). Examples include national defence, street lighting, and public fireworks. The free-rider problem means individuals have incentive to enjoy benefits without paying, causing under provision by private markets. Government provision financed through taxation solves free-rider problem but raises questions of optimal provision levels and government failure.

IB Economics real-life examples include global public goods like climate stability and pandemic preparedness requiring international cooperation, digital public goods like open-source software and Wikipedia demonstrating voluntary provision mechanisms, and debates over public broadcasting as contestable public good.

Unit 11: Asymmetric Information (HL only)

Asymmetric information exists when one party has more information than another, causing market failure through adverse selection (pre-transaction problem) and moral hazard (post-transaction problem). Used car markets demonstrate adverse selection where sellers know quality but buyers don't, leading to market collapse as only low-quality goods trade. Insurance markets face moral hazard where insured parties take more risks knowing they're protected.

Solutions include government regulation (mandatory disclosure, quality standards), signalling (warranties, certifications, education credentials), and screening (insurance questionnaires, employment probation periods). IB Economics real-life examples include financial market regulation following 2008 crisis where asymmetric information between banks and borrowers contributed to collapse, healthcare insurance market failures, and cryptocurrency market manipulation.

Unit 12: Market Power (HL only)

Monopoly power arises when single firm controls market due to barriers to entry (economies of scale, patents, control of resources, regulation). Monopolists restrict output and raise prices above marginal cost, creating deadweight welfare loss and allocative inefficiency. Monopolies may achieve productive efficiency through economies of scale and dynamic efficiency through innovation, but often exhibit X-inefficiency due to lack of competitive pressure.

Government policies include antitrust legislation and competition policy (breaking up monopolies, preventing mergers), price regulation, nationalisation, and promoting competition. IB Economics real-life examples include Big Tech platforms (Google, Amazon, Facebook) facing antitrust investigations globally, pharmaceutical patents creating temporary monopolies, and natural monopolies in utilities requiring price regulation.

Unit 13: Market's Inability to Achieve Equity (HL only)

Markets allocate resources efficiently but may produce highly unequal outcomes, with income and wealth inequality reaching historically high levels. Top 1% own 45% of global wealth while bottom 50% own just 1%. Market-generated inequality stems from differences in human capital, inherited wealth, market power, luck, and discrimination. High inequality reduces economic growth, increases social problems, and may be considered unjust.

Government redistributive policies include progressive taxation, transfer payments (unemployment benefits, pensions), provision of merit goods (education, healthcare), minimum wages, and wealth taxes. Debates focus on equity-efficiency trade-offs, optimal redistribution levels, and whether markets or governments better achieve socially desirable outcomes. Contemporary focus includes wealth inequality exacerbated by technology and globalisation, universal basic income proposals, and debates over wealth taxes in France and USA.

IB Economics Topic Integration

Microeconomic concepts underpin all subsequent economics topics. Elasticity analysis is essential for understanding tax policy and trade barriers in international economics. Market failure concepts connect to environmental sustainability, development challenges, and macroeconomic instability. Government intervention analysis in microeconomics provides foundation for evaluating macroeconomic policies. Understanding market structures and competition is critical for analysing international trade patterns and development strategies.

Key Concept Integration

Scarcity and Choice: Every market interaction reflects scarcity forcing choices. Price mechanisms allocate scarce resources among competing uses.

Efficiency and Equity: Markets achieve allocative efficiency when P=MC but may produce inequitable outcomes requiring government intervention.

Economic Well-being: Market failures like externalities and asymmetric information reduce economic well-being below potential, justifying intervention.

Sustainability: Negative externalities like pollution and common pool resource depletion threaten environmental sustainability, requiring policy responses.

Change: Technological change, preference shifts, and income growth continuously reshape demand and supply patterns.

Interdependence: Microeconomic decisions by consumers and producers are interdependent - one person's consumption affects others through externalities and market prices.

Intervention: Government microeconomic intervention can correct market failures but may create government failure through unintended consequences.

IB Economics Real-Life Examples and Case Studies

Carbon Pricing: EU ETS demonstrates tradeable permits correcting negative externality of CO2 emissions, with prices reaching €80+ per tonne.

Pharmaceutical Patents: Balance between incentivising R&D through temporary monopoly power vs. ensuring access to essential medicines in developing economies.

Housing Market Failures: Rent controls (price ceilings) in Berlin and NYC create shortages and welfare losses, while supply constraints drive prices to unsustainable levels.

Minimum Wage Debates: Price floors in labour markets create unemployment in competitive markets but may raise wages in monopsony situations without employment loss.

Electric Vehicle Subsidies: Government subsidies addressing positive externalities of reduced emissions, accelerating adoption from 2% to 18% of new car sales 2019-2024.

Study Progression Strategy

Foundation Building (Weeks 1-3)

Master fundamental demand and supply analysis, market equilibrium, and elasticity concepts. Practice diagram construction and calculation techniques.

Application Development (Weeks 4-6)

Apply theories to IB Economics real-life examples including government intervention policies, market failures, and contemporary policy debates.

Evaluation and Synthesis (Weeks 7+)

Develop sophisticated evaluation considering stakeholder perspectives, unintended consequences, and key concept connections. Practice extended response questions requiring multiple perspectives.

IB Economics Microeconomics Success:

Master diagram construction: practice demand-supply, externalities, market power, and government intervention diagrams repeatedly

Connect theory to IB Economics real-life examples: understand carbon pricing, pharmaceutical patents, housing markets, minimum wages

Develop evaluation skills: every policy has costs and benefits, intended and unintended consequences

Practice calculations: elasticity, tax incidence, welfare analysis, and deadweight loss

Use key concepts throughout analysis: scarcity, efficiency, equity, sustainability, intervention

Engage with contemporary policy debates on inequality, climate change, and market regulation

Quick Access to Microeconomics Topics

Unit 1: Demand - Law of demand, determinants, movements vs shifts

Unit 2: Supply - Law of supply, determinants, movements vs shifts

Unit 3: Competitive Market Equilibrium - Market clearing, price mechanism, surplus and shortage analysis

Unit 4: Critique of Maximising Behaviour (HL) - Bounded rationality, cognitive biases, satisficing, behavioural economics

Unit 5: Price Elasticity of Demand - PED calculation, determinants, applications to taxation and pricing

Unit 6: Income Elasticity of Demand - YED calculation, normal vs inferior goods, necessities vs luxuries

Unit 7: Price Elasticity of Supply - PES calculation, determinants, time periods

Unit 8: Government Intervention - Price controls, indirect taxes, subsidies, direct provision

Unit 9: Externalities and Common Pool Resources - Negative and positive externalities, market failure, policy responses

Unit 10: Public Goods - Non-rivalry, non-excludability, free-rider problem

Unit 11: Asymmetric Information (HL) - Adverse selection, moral hazard, market failure

Unit 12: Market Power (HL) - Monopoly, barriers to entry, welfare loss, regulation

Unit 13: Market's Inability to Achieve Equity (HL) - Income and wealth inequality, redistributive policies

Why Choose Our Microeconomics Hub?

Exam-Focused Content: Every concept designed with IB Economics assessment requirements in mind, ensuring you know exactly what matters for Papers 1, 2, and 3 (HL).

Real-World Context: From carbon pricing covering 23% of global emissions to pharmaceutical monopolies to housing market failures, we make microeconomic concepts concrete through contemporary examples.

Complete Coverage: All microeconomics topics from demand and supply through market failure and inequality, with guides covering every syllabus requirement for both SL and HL.

Contemporary Context: Updated with 2024-2025 data on carbon pricing, wealth inequality, market power, and policy debates.

Think Like an Economist: Develop the analytical reasoning and critical evaluation skills that make microeconomics a powerful tool for understanding resource allocation and market outcomes.

Diagram Mastery: Practice the graphical analysis essential for IB Economics success through step-by-step diagram construction and real-world applications.

Ready to Master Microeconomics?

Start with demand and supply fundamentals in Units 1-3, progress through elasticity concepts in Units 5-7, analyse government intervention in Unit 8, explore market failures in Units 9-10, and tackle advanced HL topics in Units 4, 11-13. Each unit builds your economic reasoning while providing analytical tools for exam excellence.

This hub is regularly updated with the latest microeconomic examples and contemporary policy debates to ensure you have the most current information for your IB Economics course.

More information about:

IB Economics Microeconomics Page

IB Economics Introduction to Economics

IB Economics The Global Economy

Read Next: IB Economics SL

© Theibtrainer.com 2012-2026. All rights reserved.

More Basic Resources For IB Students:

Legal

Have a Tip? Send us a tip using our anonymous form